Rohan M

Computer Science, Machine Learning,

Computer Vision, Music, Philosophy,

Applied Math

Why we seem to lose interest in things over time?

We like new things. We like a new start. A fresh beginning gives us a chance to put everything else aside and lets us only focus on things ahead of us - the bright future. Being an amateur at anything is exciting. The day to day progression is tangible and seeing how far you've come in a few weeks is one of the best positive reinforcements you can get about yourself. The joy of looking back and seeing progress outweighs all the people saying you suck at it.

So if you keep having this outlook, put your head down and graft, the sky is the limit, right? Seemingly not. The number of people who work hard at something is not proportional to the number of people at the absolute top of any field. As per data released by the English FA, "only 0.5% of those signed by a professional football club aged Under 9 will go all the way through to play in the first team". That is 1 in 200. And these 200 kids are the best of the best. And still you have a 1 in 200 chance to be at the top. So is this a problem in the coaching? Are the 199 out of those 200 going wrong somewhere? Is only 1 out of 200 working hard? Shouldn't more be making it if more people work hard?

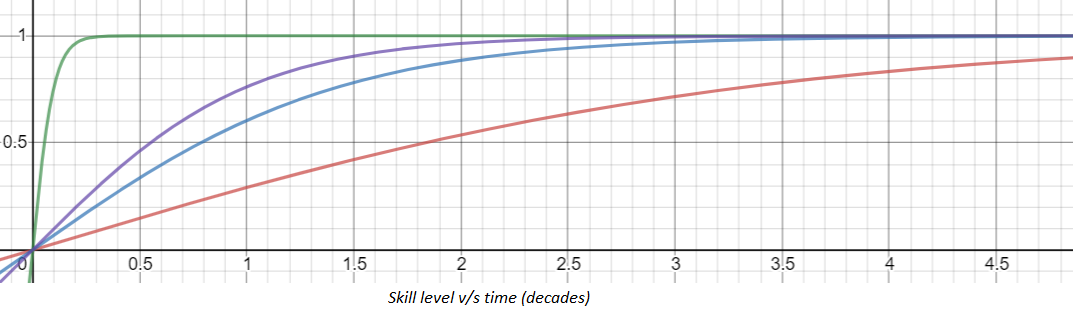

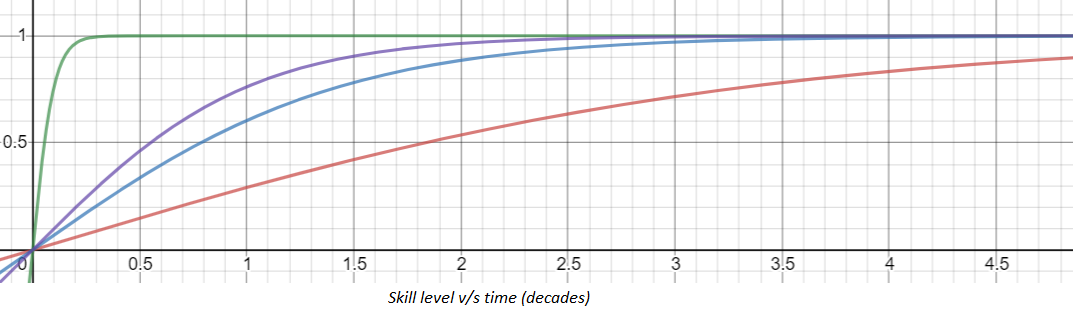

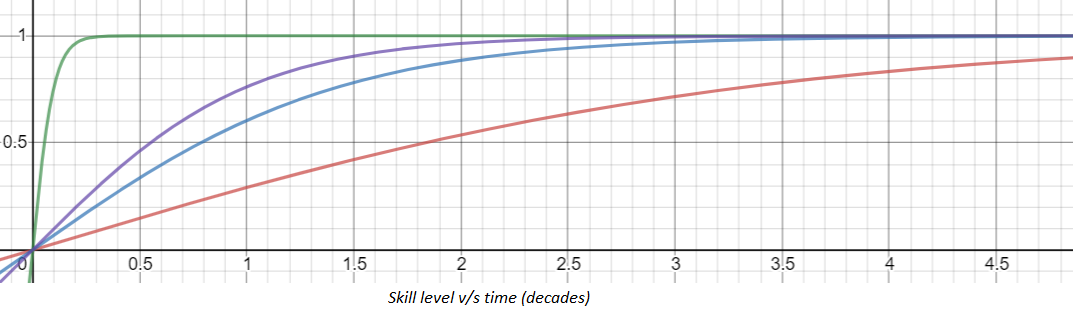

The numbers say no - grafting alone for 10-15 years isn't going to guarantee anything. The problem here is that the benefits you get from training, from putting your head down and working is not a linear function of time. The benefits keep on reducing day by day, and in a few years, the progression pretty much seems stagnant. The folks in the fitness industry call this "newbie gains". The returns from exercise, from football coaching, the knowledge you get from reading, everything goes down over time. A Nobel laureate in physics is learning much less about physics in a day than what a regular high school kid is. This is the "Law of Diminishing Returns". What ends up happening is 199 of those high school kids stop seeing the progress and lose interest and switch to something else, whereas the one becomes a Nobel laureate.

So what's causing him to be the one? The answer lies in calculus. The rate of change of these returns, aka the derivative, is different for every person and every task. A person with a higher derivative is reaching the desired skill level much sooner. The other's might still reach there, but till then its usually too late in most fields.

So is it doom and gloom for the rest of us? Do I even have a thing in which my gradient is super high? How do I even find it? Why should I even put effort in most things if I know (and I'm backed by statistics) that I'm not going to ever be the best at something?

Well, the answer in my opinion is that being the best at one thing may be great, but what's more fulfilling is to be the top 5% in the world at multiple (5+) things. Sounds unrealistic? Guess what, "newbie gains" is going to help you get there. Take programming for instance - including hobbyists, there are around 21 million people in the world who can code. Out of them, there's perhaps only a handful of John Carmacks or Jeff Deans. There are 7.8 billion people in the world, so if you've ever written a `hello world` program, you are in the top 0.26% of the world's population in programming. If you've ever pushed any code to Github, then you are in the top 0.15%. If you have a job as a professional software engineer, then you are in the top 0.03%. Every step you climb in the newbie ladder, you reach an even more exclusive club. This is true for pretty much anything. Playing the guitar, martial arts, gardening.

So why care about multiple things? Why not just stay happy at being in the top 5% of one thing? The other thing about these rewards is that it compounds over multiple things. Speaking extremely glibly, but if the measure for success in a certain field was the number of job offers you get then we can look at it this way - being a good enough programmer gets you 10 job offers and being a great one gets you 5 more exclusive roles (note that the number of more exclusive things reduces as you move to the top). But if you are a good programmer and a good gardener, then you get the first 10 job offers from each, which gets you 20 job offers.

Leaving alone this silly example, the bigger benefit of trying to get good at multiple things is that you see progress more often. Next time you feel like you aren't making as much progress doing what you do now, join a pottery class or try learning a new language. The feeling of being bad in the first few days will be overcome by the amazing progress you'll make in the first month. And personally, this feeling of knowing your efforts have paid off and you've made progress after sucking for a long time is probably more fulfilling than being the best ever at something but not really improving.

This is essentially the principle behind submodular optimization. If you have a set of items and you want to choose the most representative or the most diverse subset but there is a cost associated to how many items you choose - obviously choosing the entire set would be the most representative, but the cost would be too high. So if we smartly choose our gradients, then we only have to select a small subset which gives us the "newbie gains" and we don't have to pay as much which getting approximately optimal performance.

I co-authored some papers using this principle and applying it to computer vision if you're more of a complicated math jargon, data and numbers kind of person.

Regardless, go on, exploit the law of diminishing returns. No matter how stuck you feel right now, there are millions of things you can get exponentially better at. Suck at things today, find your right gradients, and in no time you'll (probably) be a more fulfilled person!

Computer Vision, Music, Philosophy,

Applied Math

Why we seem to lose interest in things over time?

We like new things. We like a new start. A fresh beginning gives us a chance to put everything else aside and lets us only focus on things ahead of us - the bright future. Being an amateur at anything is exciting. The day to day progression is tangible and seeing how far you've come in a few weeks is one of the best positive reinforcements you can get about yourself. The joy of looking back and seeing progress outweighs all the people saying you suck at it.

So if you keep having this outlook, put your head down and graft, the sky is the limit, right? Seemingly not. The number of people who work hard at something is not proportional to the number of people at the absolute top of any field. As per data released by the English FA, "only 0.5% of those signed by a professional football club aged Under 9 will go all the way through to play in the first team". That is 1 in 200. And these 200 kids are the best of the best. And still you have a 1 in 200 chance to be at the top. So is this a problem in the coaching? Are the 199 out of those 200 going wrong somewhere? Is only 1 out of 200 working hard? Shouldn't more be making it if more people work hard?

The numbers say no - grafting alone for 10-15 years isn't going to guarantee anything. The problem here is that the benefits you get from training, from putting your head down and working is not a linear function of time. The benefits keep on reducing day by day, and in a few years, the progression pretty much seems stagnant. The folks in the fitness industry call this "newbie gains". The returns from exercise, from football coaching, the knowledge you get from reading, everything goes down over time. A Nobel laureate in physics is learning much less about physics in a day than what a regular high school kid is. This is the "Law of Diminishing Returns". What ends up happening is 199 of those high school kids stop seeing the progress and lose interest and switch to something else, whereas the one becomes a Nobel laureate.

So what's causing him to be the one? The answer lies in calculus. The rate of change of these returns, aka the derivative, is different for every person and every task. A person with a higher derivative is reaching the desired skill level much sooner. The other's might still reach there, but till then its usually too late in most fields.

So is it doom and gloom for the rest of us? Do I even have a thing in which my gradient is super high? How do I even find it? Why should I even put effort in most things if I know (and I'm backed by statistics) that I'm not going to ever be the best at something?

Well, the answer in my opinion is that being the best at one thing may be great, but what's more fulfilling is to be the top 5% in the world at multiple (5+) things. Sounds unrealistic? Guess what, "newbie gains" is going to help you get there. Take programming for instance - including hobbyists, there are around 21 million people in the world who can code. Out of them, there's perhaps only a handful of John Carmacks or Jeff Deans. There are 7.8 billion people in the world, so if you've ever written a `hello world` program, you are in the top 0.26% of the world's population in programming. If you've ever pushed any code to Github, then you are in the top 0.15%. If you have a job as a professional software engineer, then you are in the top 0.03%. Every step you climb in the newbie ladder, you reach an even more exclusive club. This is true for pretty much anything. Playing the guitar, martial arts, gardening.

So why care about multiple things? Why not just stay happy at being in the top 5% of one thing? The other thing about these rewards is that it compounds over multiple things. Speaking extremely glibly, but if the measure for success in a certain field was the number of job offers you get then we can look at it this way - being a good enough programmer gets you 10 job offers and being a great one gets you 5 more exclusive roles (note that the number of more exclusive things reduces as you move to the top). But if you are a good programmer and a good gardener, then you get the first 10 job offers from each, which gets you 20 job offers.

Leaving alone this silly example, the bigger benefit of trying to get good at multiple things is that you see progress more often. Next time you feel like you aren't making as much progress doing what you do now, join a pottery class or try learning a new language. The feeling of being bad in the first few days will be overcome by the amazing progress you'll make in the first month. And personally, this feeling of knowing your efforts have paid off and you've made progress after sucking for a long time is probably more fulfilling than being the best ever at something but not really improving.

This is essentially the principle behind submodular optimization. If you have a set of items and you want to choose the most representative or the most diverse subset but there is a cost associated to how many items you choose - obviously choosing the entire set would be the most representative, but the cost would be too high. So if we smartly choose our gradients, then we only have to select a small subset which gives us the "newbie gains" and we don't have to pay as much which getting approximately optimal performance.

I co-authored some papers using this principle and applying it to computer vision if you're more of a complicated math jargon, data and numbers kind of person.

Regardless, go on, exploit the law of diminishing returns. No matter how stuck you feel right now, there are millions of things you can get exponentially better at. Suck at things today, find your right gradients, and in no time you'll (probably) be a more fulfilled person!

Why we seem to lose interest in things over time?

We like new things. We like a new start. A fresh beginning gives us a chance to put everything else aside and lets us only focus on things ahead of us - the bright future. Being an amateur at anything is exciting. The day to day progression is tangible and seeing how far you've come in a few weeks is one of the best positive reinforcements you can get about yourself. The joy of looking back and seeing progress outweighs all the people saying you suck at it.

So if you keep having this outlook, put your head down and graft, the sky is the limit, right? Seemingly not. The number of people who work hard at something is not proportional to the number of people at the absolute top of any field. As per data released by the English FA, "only 0.5% of those signed by a professional football club aged Under 9 will go all the way through to play in the first team". That is 1 in 200. And these 200 kids are the best of the best. And still you have a 1 in 200 chance to be at the top. So is this a problem in the coaching? Are the 199 out of those 200 going wrong somewhere? Is only 1 out of 200 working hard? Shouldn't more be making it if more people work hard?

The numbers say no - grafting alone for 10-15 years isn't going to guarantee anything. The problem here is that the benefits you get from training, from putting your head down and working is not a linear function of time. The benefits keep on reducing day by day, and in a few years, the progression pretty much seems stagnant. The folks in the fitness industry call this "newbie gains". The returns from exercise, from football coaching, the knowledge you get from reading, everything goes down over time. A Nobel laureate in physics is learning much less about physics in a day than what a regular high school kid is. This is the "Law of Diminishing Returns". What ends up happening is 199 of those high school kids stop seeing the progress and lose interest and switch to something else, whereas the one becomes a Nobel laureate.

So what's causing him to be the one? The answer lies in calculus. The rate of change of these returns, aka the derivative, is different for every person and every task. A person with a higher derivative is reaching the desired skill level much sooner. The other's might still reach there, but till then its usually too late in most fields.

So is it doom and gloom for the rest of us? Do I even have a thing in which my gradient is super high? How do I even find it? Why should I even put effort in most things if I know (and I'm backed by statistics) that I'm not going to ever be the best at something?

Well, the answer in my opinion is that being the best at one thing may be great, but what's more fulfilling is to be the top 5% in the world at multiple (5+) things. Sounds unrealistic? Guess what, "newbie gains" is going to help you get there. Take programming for instance - including hobbyists, there are around 21 million people in the world who can code. Out of them, there's perhaps only a handful of John Carmacks or Jeff Deans. There are 7.8 billion people in the world, so if you've ever written a `hello world` program, you are in the top 0.26% of the world's population in programming. If you've ever pushed any code to Github, then you are in the top 0.15%. If you have a job as a professional software engineer, then you are in the top 0.03%. Every step you climb in the newbie ladder, you reach an even more exclusive club. This is true for pretty much anything. Playing the guitar, martial arts, gardening.

So why care about multiple things? Why not just stay happy at being in the top 5% of one thing? The other thing about these rewards is that it compounds over multiple things. Speaking extremely glibly, but if the measure for success in a certain field was the number of job offers you get then we can look at it this way - being a good enough programmer gets you 10 job offers and being a great one gets you 5 more exclusive roles (note that the number of more exclusive things reduces as you move to the top). But if you are a good programmer and a good gardener, then you get the first 10 job offers from each, which gets you 20 job offers.

Leaving alone this silly example, the bigger benefit of trying to get good at multiple things is that you see progress more often. Next time you feel like you aren't making as much progress doing what you do now, join a pottery class or try learning a new language. The feeling of being bad in the first few days will be overcome by the amazing progress you'll make in the first month. And personally, this feeling of knowing your efforts have paid off and you've made progress after sucking for a long time is probably more fulfilling than being the best ever at something but not really improving.

This is essentially the principle behind submodular optimization. If you have a set of items and you want to choose the most representative or the most diverse subset but there is a cost associated to how many items you choose - obviously choosing the entire set would be the most representative, but the cost would be too high. So if we smartly choose our gradients, then we only have to select a small subset which gives us the "newbie gains" and we don't have to pay as much which getting approximately optimal performance.

I co-authored some papers using this principle and applying it to computer vision if you're more of a complicated math jargon, data and numbers kind of person.

Regardless, go on, exploit the law of diminishing returns. No matter how stuck you feel right now, there are millions of things you can get exponentially better at. Suck at things today, find your right gradients, and in no time you'll (probably) be a more fulfilled person!